Late last week two great blog posts were released with seemingly opposite titles. “Don’t Build Multi-Agents” by the Cognition team, and “How we built our multi-agent research system” by the Anthropic team.

Despite their opposing titles, I would argue they actually have a lot in common and contain some insights as to how and when to build multi-agent systems:

- Context engineering is crucial

- Multi-agent systems that primarily “read” are easier than those that “write”

Context engineering is critical

One of the hardest parts of building multi-agent (or even single-agent) applications is effectively communicating to the models the context of what they’re being asked to do. The Cognition blog post introduces the term “context engineering” to describe this challenge.

In 2025, the models out there are extremely intelligent. But even the smartest human won’t be able to do their job effectively without the context of what they’re being asked to do. “Prompt engineering” was coined as a term for the effort needing to write your task in the ideal format for a LLM chatbot. “Context engineering” is the next level of this. It is about doing this automatically in a dynamic system. It takes more nuance and is effectively the #1 job of engineers building AI agents.

They show through a few toy examples that using multi-agent systems makes it harder to ensure that each sub-agent has the appropriate context.

The Anthropic blog post doesn’t explicitly use the term context engineering, but at multiple points it addresses the same issue. It’s clear that the Anthropic team spent a significant amount of time on context engineering. Some highlights below:

Long-horizon conversation management. Production agents often engage in conversations spanning hundreds of turns, requiring careful context management strategies. As conversations extend, standard context windows become insufficient, necessitating intelligent compression and memory mechanisms. We implemented patterns where agents summarize completed work phases and store essential information in external memory before proceeding to new tasks. When context limits approach, agents can spawn fresh subagents with clean contexts while maintaining continuity through careful handoffs. Further, they can retrieve stored context like the research plan from their memory rather than losing previous work when reaching the context limit. This distributed approach prevents context overflow while preserving conversation coherence across extended interactions.

In our system, the lead agent decomposes queries into subtasks and describes them to subagents. Each subagent needs an objective, an output format, guidance on the tools and sources to use, and clear task boundaries. Without detailed task descriptions, agents duplicate work, leave gaps, or fail to find necessary information.

Context engineering is critical to making agentic systems work reliably. This insight has guided our development of LangGraph, our agent and multi-agent framework. When using a framework, you need to have full control what gets passed into the LLM, and full control over what steps are run and in what order (in order to generate the context that gets passed into the LLM). We prioritize this with LangGraph, which is a low-level orchestration framework with no hidden prompts, no enforced “cognitive architectures”. This gives you full control to do the appropriate context engineering that you require.

Multi-agent systems that primarily “read” are easier than those that “write”

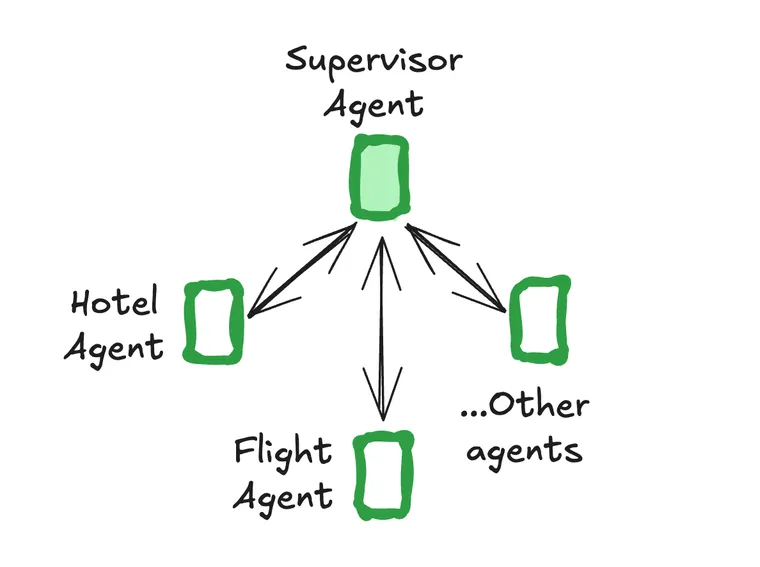

Multi-agent systems designed primarily for "reading" tasks tend to be more manageable than those focused on "writing" tasks. This distinction becomes clear when comparing the two blog posts: Cognition's coding-focused system and Anthropic's research-oriented approach.

Both coding and research involve reading and writing, but they emphasize different aspects. The key insight is that read actions are inherently more parallelizable than write actions. When you attempt to parallelize writing, you face the dual challenge of effectively communicating context between agents and then merging their outputs coherently. As the Cognition blog post notes: "Actions carry implicit decisions, and conflicting decisions carry bad results." While this applies to both reading and writing, conflicting write actions typically produce far worse outcomes than conflicting read actions. When multiple agents write code or content simultaneously, their conflicting decisions can create incompatible outputs that are difficult to reconcile.

Anthropic's Claude Research illustrates this principle well. While the system involves both reading and writing, the multi-agent architecture primarily handles the research (reading) component. The actual writing—synthesizing findings into a coherent report—is deliberately handled by a single main agent in one unified call. This design choice recognizes that collaborative writing introduces unnecessary complexity.

However, even read-heavy multi-agent systems aren't trivial to implement. They still require sophisticated context engineering. Anthropic discovered this firsthand:

We started by allowing the lead agent to give simple, short instructions like 'research the semiconductor shortage,' but found these instructions often were vague enough that subagents misinterpreted the task or performed the exact same searches as other agents. For instance, one subagent explored the 2021 automotive chip crisis while 2 others duplicated work investigating current 2025 supply chains, without an effective division of labor.

Production reliability and engineering challenges

Whether using multi-agent systems or just a complex single agent one, there are several reliability and engineering challenges that emerge. Anthropic's blog post does a great job of highlighting these. These challenges are not unique to Anthropic's use case, but are actually pretty generic. A lot of the tooling we've been building has been aimed at generically solving problems like these.

Durable execution and error handling

Agents are stateful and errors compound. Agents can run for long periods of time, maintaining state across many tool calls. This means we need to durably execute code and handle errors along the way. Without effective mitigations, minor system failures can be catastrophic for agents. When errors occur, we can't just restart from the beginning: restarts are expensive and frustrating for users. Instead, we built systems that can resume from where the agent was when the errors occurred.

This durable execution is a key part of LangGraph, our agent orchestration framework. We believe all long running agents will need this, and accordingly it should be built into the agent orchestration framework.

Agent Debugging and Observability

Agents make dynamic decisions and are non-deterministic between runs, even with identical prompts. This makes debugging harder. For instance, users would report agents “not finding obvious information,” but we couldn't see why. Were the agents using bad search queries? Choosing poor sources? Hitting tool failures? Adding full production tracing let us diagnose why agents failed and fix issues systematically.

We have long recognized that observability for LLM systems is different than traditional software observability. A key reason why is it needs to be optimized for debugging these types of challenges. If you’re not sure what exactly this means - check out LangSmith, our platform for (among other things) agent debugging and observability. We’ve been building LangSmith for the past two years to handle these types of challenges. Try it out and see why this is so critical!

Evaluation of agents

A whole section in the Anthropic post is dedicated to “effective evaluation of agents”. A few key takeaways that we like:

- Start small with evals, even ~20 datapoints is enough

- LLM-as-a-judge can automate scoring of experiments

- Human testing remains essential

This resonates whole-heartedly with our approach to evaluation. We’ve been building evals into LangSmith for a while, and have landed on several features to help with those aspects:

- Datasets, to curate datapoints easily

- Running LLM-as-a-judge server side (more features coming here soon!)

- Annotation queues to coordinate and facilitate human evaluations

Conclusion

Anthropic’s blog post also contains some wisdom for where multi-agent systems may or may not work best:

Our internal evaluations show that multi-agent research systems excel especially for breadth-first queries that involve pursuing multiple independent directions simultaneously.

Multi-agent systems work mainly because they help spend enough tokens to solve the problem…. Multi-agent architectures effectively scale token usage for tasks that exceed the limits of single agents.

For economic viability, multi-agent systems require tasks where the value of the task is high enough to pay for the increased performance.

Further, some domains that require all agents to share the same context or involve many dependencies between agents are not a good fit for multi-agent systems today. For instance, most coding tasks involve fewer truly parallelizable tasks than research, and LLM agents are not yet great at coordinating and delegating to other agents in real time. We’ve found that multi-agent systems excel at valuable tasks that involve heavy parallelization, information that exceeds single context windows, and interfacing with numerous complex tools.

As is quickly becoming apparent when building agents, there is not a “one-size-fits-all” solution. Instead, you will want to explore several options and choose the best one according to the problem you are solving.

Any agent framework you choose should allow you to slide anywhere on this spectrum - something we’ve uniquely emphasized with LangGraph.

Figuring out how to get multi-agent (or complex single agent) systems to function also requires new tooling. Durable execution, debugging, observability, and evaluation are all new tools that will make your life as an application developer easier. Luckily, these are all generic tooling. This means that you can use tools like LangGraph and LangSmith to get these off-the-shelf, allowing you to focus more on the business logic of your application than generic infrastructure.